The Early Years

Childhood. Starting my first job.

I am carrying a strong desire to look for opportunities to grow myself, others and businesses.

1969 - 1986

Jakobstad, Finland

Childhood. Starting my first job.

1987 - 1990

Jakobstad, Finland

Graduation. Golden Invest. Military service.

1990 - 1992

Jakobstad, Finland

This is where it happens! 2 years; all up, all down, Crashed & burned. The Best School Ever.

1993 - 1995

Stockholm, Sweden

Exposed to "life". Learning about people.

1995 - 1998 (-2003)

Stockholm, Sweden

Did all, learned it all, systematic profits were the takeaway.

1998 - 1999

Stockholm, Sweden

It works!

1999 - 2008

Stockholm, Sweden

IKEA Barkarby store: Improving the Check-Out Operations, Adding to the IKEA Concept, Business Navigation: €100M Budget x 4. Safety & Security, a fore-runner. The birth of IKEA staff planning.

2008 - 2010

Yekaterinburg, Russia

Real success. Tasting Good! A Family Milestone.

2010 - 2012

Khimki, Moscow, Russia

Size & impact.

2012 - 2015

Khimki, Moscow, Russia

Establishing the Risk function for IKEA Retail. The most exciting job ever... WOW. What a blast!

2015 - 2017

London, UK

Opening new units in the UK and Ireland.

2017 - 2019

Yekaterinburg, Russia

Entrepreneurship, English Clubs, and a New Chapter

2019 -

Stockholm, Sweden

Building from the ground up—with care, ambition, and commitment.

Jakobstads Handelsläroverk as it looks around 1990

Golden-Invest

By 1987, global stock markets had been booming for a few years. That autumn, I registered my second business—Golden-Invest—which acted as a small holding company for trading stocks on the Helsinki Stock Exchange. While the business volume was modest, the returns were strong (relatively speaking). The performance had more to do with the bullish market than with any genius on my part—but it worked.

I had been dabbling in stock investments since 1984, but this was the first time I structured it under a formal business entity.

Golden-Invest and I briefly made headlines when I used direct mail marketing to acquire shares in Sampo, a major national insurance company.

Sampo was preparing to list on the Helsinki Stock Exchange and began distributing shares to their policyholders—many of whom held small, almost symbolic insurance policies. In effect, nearly every Finnish household would soon own a single share in Sampo.

My idea was straightforward: I bet that most people wouldn’t be interested in managing just one unlisted share—especially those with no prior experience in stocks. And since no price had been set yet, my cash offers would likely appear as a windfall.

At 18, and using a rather unconventional method—direct mail marketing—I caught the attention of both local and national newspapers. Golden-Invest was completely unknown in the financial world, and there was some wild (and entirely unfounded) speculation about a potential hostile takeover attempt.

The campaign worked to a degree. I did acquire some shares this way, and the investment paid off—around a 5x return, if memory serves. Not bad for a teenager with a copying machine, an idea, and a bit of nerve.

The idea of running a “brick-and-mortar” business had started to take shape…

While still studying, I was offered a seat on the board of the student organisation. Serving as both board member and treasurer gave me the chance to oversee and manage the student café. It wasn’t rocket science—anyone who’s ever been a customer can grasp the basics—but it was practical experience and, more importantly, it inspired me. I saw the margins in the restaurant business, and I was intrigued.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Business Administration in 1988, I worked as a delivery driver for a currier service. Later that year, I left for eight months of mandatory military service.

Photo from summer 1991: Back when lunch cost €4.00 ($4.67) and petrol was €0.47/litre ($2.08/gallon). The old Union-branded station was rebranded as S-24, with the retail premises renamed City Café.

Going Up: City Café & S-24

The old Union station was transitioning from a full-service model to a 24-hour automated station—S-24—with an adjacent independent café/diner called City Café.

After successful negotiations, we took over operations in November 1990. Our existing business (Café Relax and Beda Kantin) now included City Café and the S-24 petrol station.

City Café was a full diner with 50 seats, a table tennis room, an outdoor walk-up window, arcade games, and slot machines. It was open daily from 7:00 to 01:00. At its peak, we employed 11 people. Both of us—at just 21 years old—were now full-time operators of a relatively large and dynamic business.

Taking market shares for NESTE

At the time, Jakobstad had 11 different petrol retailers. When we took over the S-24 station, it ranked 10th in sales volume.

With the flexibility of our NESTE contract, we adopted an aggressive pricing strategy. In just three months, we rose from 10th to 2nd place in the local fuel market. We held that position for the next 18 months, from March 1991 until we exited in September 1992, with annual sales reaching nearly 950,000 litres (250,000 gallons).

The Struggle

Our key profit sources were fuel sales and commissions from arcade and slot machines. But the rapid expansion of the business had left us financially strained. Cash flow became tight.

In 1991, I bought out my friend and became the sole owner. I managed to turn the restaurant side of the business profitable, but…

Going down

… the early losses had been too deep, and we had grown too fast. In early 1992, I was forced to shut down the restaurant operations. I kept the S-24 petrol station running until September of that year before stepping away completely.

A lot of work & learning... in a short time

In 1991 alone, I logged a staggering 5,200 working hours. For comparison, a full-time job amounts to about 1,900 hours per year.

That’s nearly three years’ worth of work packed into one.

It was intense, it was exhausting—and it was the best education I could have ever received.

In 1992, Finland entered a deep recession following the collapse of the Soviet Union—its most important trading partner. Unemployment soared, especially among the young, with as many as one in four people under the age of 25 out of work. Staying was not a viable option.

So, in late January 1993, my best friend and I left Jakobstad, Finland, for Stockholm, Sweden, in search of a better future.

Arriving in Stockholm, I was determined to truly understand the restaurant business. I began working at Tre Remmare, a nightclub in central Stockholm. Coming from a small town like Jakobstad, this move alone was a big step—but working at a busy city nightclub opened my eyes in a whole new way. I observed a wider range of people, lives, and stories than I’d ever encountered before.

Tre Remmare was located on Vasagatan 7, near Stockholm Central Station. At the time, it was one of the largest restaurants in the city—open every day of the year, from 11 a.m. to 5 a.m. It was there that I learned how a traditional restaurant truly operated—but more than that, I learned about people.

I started as a busboy and eventually worked in the bar and as a waiter. During summer, we served up to 4,000 beers a day from a 29-metre (95 ft) bar—around 1,900 litres (500 gallons) of beer daily, seven days a week. That’s impressive by any standard.

Today, the bar still exists but has been redesigned and now operates under the name The Bishop’s Arms.

I worked at Tre Remmare from 1993 to 1995, gaining invaluable experience and enjoying every moment, thanks to an outstanding team. It was a place where everyone felt welcome and respected—and the guests could feel that too.

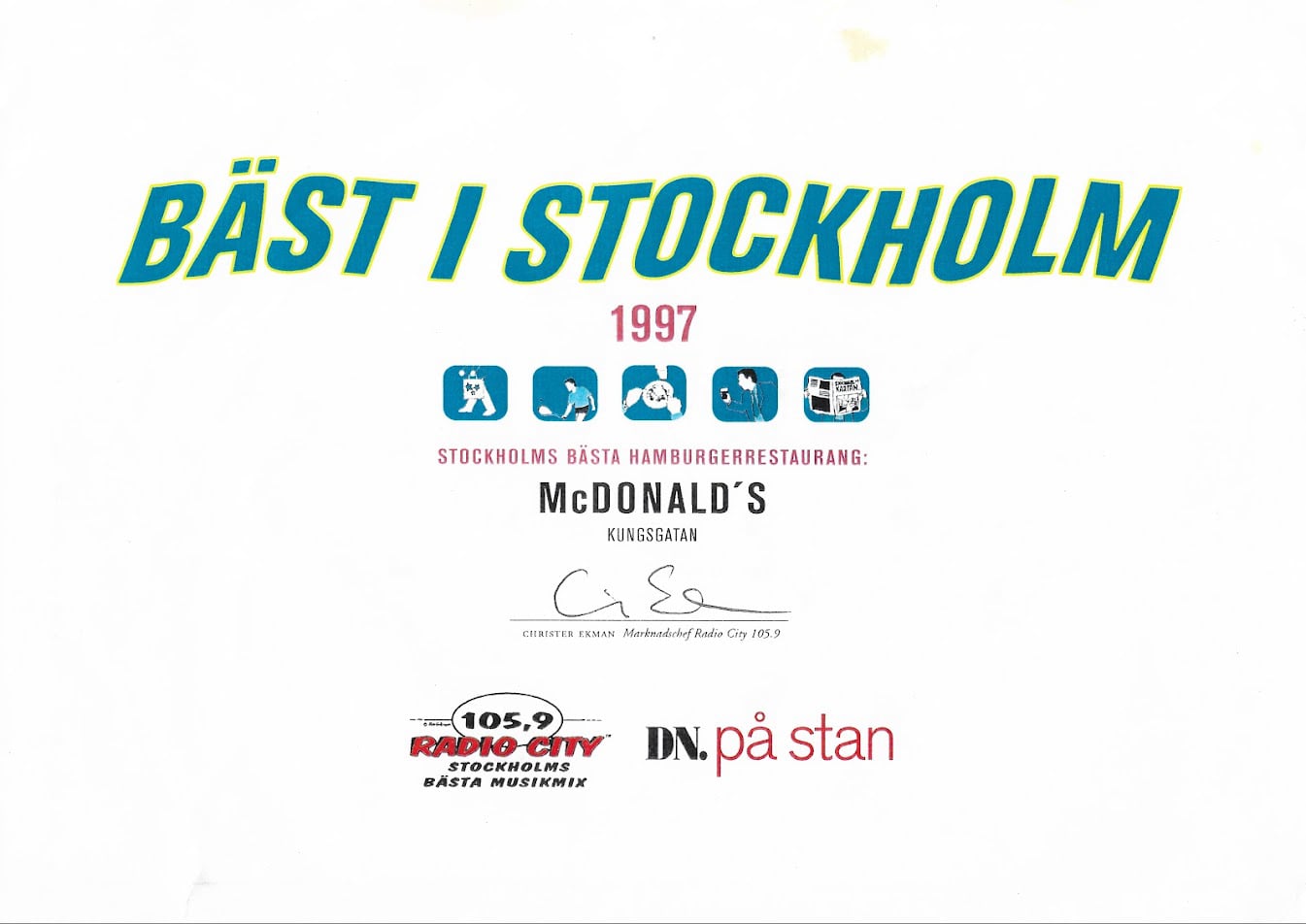

For many, McDonald’s is a first job. I was 26 when I joined Sweden’s first McDonald’s location—opened in 1973—at Kungsgatan 4, Stockholm. By then, it was a franchise, and the owners had been operating it since 1986. I can still say, without hesitation, that this was the best employer I’ve ever had.

I started in the kitchen making cheeseburgers. After day one, I was certain I’d made a mistake and wanted to quit. But something made me come back for day two.

That second day changed everything. I realised that this was unlike any other business I’d encountered—not even remotely similar to my previous ventures or Tre Remmare. Everything at McDonald’s was documented. Targets were set and followed up. They knew their profit margin every hour, on the hour. Revenue and costs were monitored in real time. I was amazed.

That’s when I made the decision: I had to understand how this system worked before I left. So I stayed—for exactly three years, leaving in 1998 to take on a new challenge at Kantin Moneo.

Some of my closest friends today are people I met at McDonald’s.

My takeaway...

In 1998, I left McDonald’s to become the Restaurant Manager at Kantin Moneo. My mission: implement the McDonald’s system in a traditional restaurant setting.

Kantin Moneo was located inside the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moderna Museet) at Skeppsholmen in central Stockholm. Owned by renowned restaurateurs Olle Lindberg and Carl Jan Granqvist, it included:

- A large self-service restaurant

- An à la carte restaurant

- An exclusive bar at the adjacent Architecture Museum, called Bloms Bar

- Extensive conference and event catering (three-course dinners for up to 400 guests)

Once, in autumn 1998, we served 750 guests simultaneously—400 in the restaurant and 350 in the conference centre.

Frequent guests included Sweden’s social and cultural elite: King Carl XVI Gustaf, Prime Minister Göran Persson, other members of the royal court and government, and CEOs of major Swedish companies such as Ericsson’s Ramqvist. The self-serve restaurant also welcomed countless museum visitors—locals and tourists alike.

It worked!!

This was an exciting time. My goal was to bring profitability and structure to the newly opened restaurant, and I consider the outcome a success.

IKEA Barkarby store: Improving check-out operations, adding to the IKEA Concept, business navigation: €100M budget x4, safety & security leadership, and the birthplace of IKEA Staff Planning.

After 11 years in the restaurant industry, I felt I had little left to prove. It was time to move on—to retail.

By then, I had solid operational experience, strong leadership skills, and a deep ambition to “systematically make profits”. I was convinced there was more to learn, and more to improve, in the world of retail.

I chose IKEA, drawn by its unique concept and extraordinary success. The founder, Ingvar Kamprad, built one of the world’s largest retail brands without ever listing the company on the stock market. IKEA has remained privately held, reinvesting profits into its own growth—a model I found both inspiring and aligned with my thinking.

Improving the Check-Out operations

I joined IKEA Barkarby in 1999 as Deputy Check-Out Manager.

While IKEA was already a powerhouse in purchasing, logistics, and the sales concept, I saw untapped potential in the areas of administration and operational control.

From the start, I focused on co-worker scheduling and training. Alongside my team in the check-out department, we reorganised recruitment and staff planning to be far more flexible and effective.

We also developed and implemented new security-focused training. Much of that programme was used for years afterwards—possibly even today. At its peak, we managed over 100 cashiers in the check-out team.

IKEA - Adding to the IKEA concept

In 2001, I was invited to participate in a global IKEA project aimed at recovering the cost of returned goods—a concept first developed at IKEA Seattle.

Our task was to test and refine this process across four European stores, with the goal of reducing loss and recovering value—eventually turning it into a new IKEA department.

I served as Project Leader and Department Manager for the Recovery Department at IKEA Barkarby, one of the four pilot stores selected for the initiative. The project was financed directly by IKEA Europe’s regional headquarters.

For a year, we ran, documented, and refined the operation. The pilot was a success, and the resulting process became the newest addition to the IKEA Concept:

“Working with Recovery – The IKEA Way”.The process was rolled out globally in 2002–2003. I continued as Shopkeeper for Recovery in Barkarby.

The Recovery concept added roughly 10% to IKEA Group’s bottom line, year after year. It also pushed store controlling forward and laid the groundwork for what would become IKEA Sustainability. Today, it’s regarded as one of the top 10 most important additions to the IKEA Concept in the past two decades.

Visitors know it as the “Bargain Corner” or “As-Is”—or, in Sweden, “Fynd”.

Safety & Security

From 2004 to 2008, I served as Store Safety & Security Manager at IKEA Barkarby.

The role was broad and meaningful: preventing and investigating internal and external fraud, and ensuring safety against fire hazards, accidents, and other risks.

Under my leadership, the store moved from a strong baseline to becoming a national leader in IKEA’s Safety & Security standards. I was invited to contribute to training other IKEA stores in Sweden and Russia, including coaching Country Safety & Security Managers.

In 2007, I developed an Excel VBA tool for monitoring cashier performance. It collected real-time statistics, flagged suspicious patterns, and highlighted team members who needed coaching. The tool was adopted across all IKEA stores in Sweden in 2007 and was a key advancement in performance follow-up.

Our success in Barkarby was built on clear leadership and strong follow-through—making safety and security an integrated part of every co-worker’s role.

While my main role was in safety and business navigation, I had never let go of my McDonald’s background in staff planning. That knowledge was always there, quietly influencing my work.

In 2005, I illustrated McDonald’s staff planning principles on a whiteboard in a meeting room at IKEA Barkarby (named TUNNAN). I compared IKEA’s state in 2005 with what I had seen in McDonald’s in 1996—using their legendary forecasting tool, McSchema.

Even earlier, between 2001 and 2003, while leading Recovery, I had started experimenting with staff planning in Excel—based directly on McSchema principles.

But 2005 was the turning point. That conversation with my colleague—who would later become my Store Manager in Yekaterinburg, Russia—sparked something.

Together, we began testing how IKEA could implement need-based staffing. Our work inspired other stores to experiment as well.

2006 - SWEDEN

In 2006, IKEA Sweden formally dedicated resources to staff planning. The first national tool was named “BAB” (BehovsAnpassadBemanning – or “Need-Based Staffing”).

It followed the same principles I had learned at McDonald's: matching workload with staffing in a dynamic, data-driven way.

Though early versions had limitations, this was a vital first step.

2008 - RUSSIA

When we moved to IKEA Yekaterinburg, we had greater freedom to develop the concept further. Our version of staff planning matured significantly, and with the support of my Store Manager, the project was approved for national rollout in Russia.

A dedicated project manager joined our store, and we developed and tested the model in Yekaterinburg. By 2010, all IKEA stores in Russia were using our system.

When I transferred to IKEA Khimki, I continued refining the process and supported national and even occasional global implementation.

Our Staff Planning Teams in Yekaterinburg and Khimki were key to this development from 2008 to 2012.

HARVESTING THE RESULTS

Done right, Human Resource Planning benefits everyone—co-workers and customers alike.

In Russia, our approach to staff planning helped fuel the rapid growth of IKEA stores in both footfall and sales. It delivered operational efficiency while improving service quality.

2011 - IKEA WORLD

Other IKEA countries began recognising the potential.

By 2012, when I transitioned into a new global role in Risk Management, staff planning was on the agenda in several national organisations—though Russia still led the way.

By 2015, exactly 20 years after I had first worked with McSchema at McDonald’s, IKEA had built a global matrix organisation supporting staff planning worldwide.

I’m incredibly proud to have initiated and inspired that journey. It remains one of my greatest contributions at IKEA.

I actually never had staff planning as my main role, but it was by my side all the way since McDonald's. I did not contribute anything to the development of the IKEA staff planning after 2012, but I have personally created the training material and trained many of the people now working with staff planning inside and outside IKEA in many countries around the world.

IKEA's approach to Staff Planning was born in Barkarby in 2005, that's when and where it all began. Now you know.

A Legacy Built on Passion

Although staff planning was never my official job title, it was always by my side—from McDonald’s in 1995 to IKEA’s global operations by 2015.

I created training materials, mentored professionals, and helped embed staff planning in IKEA stores across Sweden, Russia, and beyond.

IKEA's approach to Staff Planning was born in Barkarby in 2005.

Now you know where it all began.

Photo of customers queuing at 44 open [all] check-outs at 00:19 on Sunday, 5 June 2016. The store, open from 10:00 to 02:00, operates 365 days a year. Taken while shopping for a METOD kitchen.

In September 2010, I was assigned to IKEA Khimki, just outside Moscow, as Business Navigation & Operations Manager.

At the time, IKEA Khimki was:

- The largest IKEA store in the world by turnover (EUR and m³) tied with IKEA Teply Stan in the southern part of Moscow.

- A global IKEA flagship, home to IKEA Russia's headquarters (on its roof!)

- A frequent destination for internal visitors from all corners of IKEA’s global operations

In fact, monthly EBIT profit from Khimki exceeded the annual EBIT of all 17 IKEA stores in the UK at the time. Khimki also generated more turnover than all the IKEA stores in Finland or Portugal combined. Yes, I take great pride in that.

Managing operations at such a massive, high-pressure store—often underdimensioned for its commercial load—was incredibly challenging. But with a team of 1,200 fantastic people, we made it happen.

My contributions involved pushing operational limits within existing constraints, while maintaining safety and structure. The methods I applied had been proven earlier—at Yekaterinburg, Barkarby, Kantin Moneo, and even McDonald’s. But as always, it was the people, working together, who turned challenge into success.

As IKEA’s founder, Ingvar Kamprad, once said:

“Most things remain to be done. Wonderful future.”

Before My Arrival

IKEA Russia launched its first store in Khimki, Moscow on 22 March 2000. Even before that, a Safety & Security function was in place.

Between 2000 and 2009, IKEA Russia expanded rapidly—not only in retail, but also in property development, building large-scale shopping centres. By 2011, 13 centres had been constructed. Samara opened as the 14th that year.

Until 2012, there was just one centralised Risk function, covering shopping centres, stores, warehouses, and factory sites. IKEA Industry (formerly Swedwood) had its own Risk unit, based outside Russia.

This central function focused primarily on property, not retail—understandable, given that shopping centres are roughly five times the size of IKEA stores.

Starting point...

While working in the Yekaterinburg and Khimki stores, I frequently highlighted the lack of IKEA retail competence in the existing Risk organisation.

As a result, in June 2012, I was appointed Country Risk Manager for IKEA Retail Russia, tasked with establishing a dedicated retail-focused Risk organisation.

Responsibilities included:

- 14 IKEA stores

- 1 Distribution Centre

- 1 Furniture Factory

- 3 Sourcing Offices (Novosibirsk, Kiev, Minsk)

- The Russia Service Office (HQ) located above IKEA Khimki

In total:

- Over 500,000 m² of rented retail space

- More than 10,000 employees

- 300 loading bays, 500 forklifts, and 250 delivery trucks daily

- Movement of 3 million m³ of goods annually

- Nearly 200,000 daily visitors, 365 days a year

It was anything but a small task.

The pictures above give some flavor of what this assignment contained.

Objective

The core objective was simple and critical:

Ensure IKEA Retail Russia could detect, react to, and prevent all forms of risk that might hinder business continuity or growth.

This was not a consultancy. I had a clear mandate to take operational leadership and drive change.

'Meeting the Customer' Focus

I'm very proud of the introduction of retail only risk organization that comes from, works in and for the stores. I set out to convince and promote what I called the Retail Risk Direction, containing 5 keywords around which the change was launched. All aiming to integrate the IKEA retail thinking and needs of a meeting the customer focus when working with Safety & Security.

To really crystalize the focus, I initiated a split of the risk organization, so that the distribution and sourcing parts of IKEA Russia got their own independent risk function as well, making it 3 independent risk organizations working for IKEA Russia, in addition to the IKEA Industry Risk function working for Russia from Sweden.

Leaving IKEA Russia for the UK organization, I handed over the Risk function in the hands of a previous Restaurant Manager turned Country Safety & Security Manager. I'm very happy with the change and shift of focus achieved, returning it back to the IKEA shop floor for the benefit of IKEA shoppers.

What were the main challenges?

Compliance

Compliance with the laws and regulations can be very challenging and demanding. The chosen approach to address this was focusing on change of mindset internally, preparedness with more internal reviews and checks, increased knowledge about what to comply with and why.

The general compliance measured in reviews and visits by authorities showed a very good development. So good, in fact, that I changed the Compliance keyword in my Retail Risk Direction strategy to Systematic, indicating the next level of challenge.

Reporting

To get the people in all parts of the organization to systematically report and document detected issues was a very important barrier to overcome. Having a systematic reporting process is the base for any consistent and systematic work with prevention.

The ability to document and record reports increased dramatically. Again, clearly communicated expectations, good support & guidance, and strong follow-up was the main game changer.

Corruption

The challenge with corruption lies in the ability to detect and recognize it. I reached a good level of understanding corruption on the Russian market, but I am sorry to say that very little was moved forward on this topic passed the level of reaction on detected cases.

The types of corruption IKEA Retail in Russia was exposed to, is usually visible through low quality in maintenance and construction works, but also in more classic areas such as embezzlement and fraud. Example of severe consequences of corruption can be fires, electrical accidents, and failing equipment systems etc..

External theft and fraud is a smaller problem at IKEA in Russia than in other countries in Europe and overall a relatively small issue compared to other retailers.

Unforeseen Event Handling

All big corporations have some type of Crisis or Emergency Management structure in place to handle situations that the normal business structures are not intended for.

At IKEA this is designed globally, mostly based on context expectations more relevant to the stability of, for instance, the UK or Sweden, rather than for the more vibrant and vivid business life in Russia.

This made me craft a simplified version of the internal global expectations on defining emergencies and crisis. Basically, the approach was to downsize the grade, as the running business organization in all units are much more resilient, experienced and better equipped to react to unforeseen events.

Instead of working with a full scale, crisis management or emergency response team, I usually satisfied with something I called, Focus Groups, smaller constellations of a couple of people spontaneously put together depending on the need of the day.

It was not possible to tie up large parts of the most senior management for all the events that would fit the European designed structure. I was very content with the efficiency, flexibility, and capacity that was the effect, but I am aware that it occasionally caused some annoyance in the IKEA organization outside Russia.

In the end, it was a very successful approach and I am very thankful for the mandate, support, and freedom I had, to work with what could be called Unforeseen Event Handling. In the right context, this approach could work in other places too.

After seven years in Russia, I jumped at the opportunity to trade Moscow for London. In hindsight, maybe I shouldn’t have—but I’m still very glad I did.

I took on the role of Country Risk Manager for IKEA UK and Ireland, arriving in London with my family at the end of August 2015. My wife was pregnant at the time, and our daughter was three years old.

Starting a new life in London was an amazing experience. Our son was born just two months later—in Westminster, no less. Our daughter began her first school year at the International School of London in Ealing, where she quickly picked up English.

Professionally, it was an intense and rewarding period. From a Risk perspective, I led the work during the launch of:

- Six new smaller-format retail units (Order & Collection Points)

- Two full-size IKEA stores – Reading and Sheffield

Opening a new IKEA unit is a major undertaking in any context. Doing it multiple times in under two years—with limited resources—was a significant achievement. I’m proud of the work we did, and grateful to the many incredible colleagues and teams who made it all happen. It was exhilarating to be part of so much expansion in such a short span of time.

However, we encountered an unexpected challenge: visa complications affecting some members of my family.

This clouded much of our time in the UK. The uncertainty made it difficult to settle in properly, plan ahead, or travel freely. As time went on, the lack of resolution became more than just an inconvenience—it became a constant source of stress and limitation.

In our second year, with no clear timeline for a solution, I made the difficult decision to leave London.

It wasn’t easy to walk away, but as always—big changes give rise to new beginnings. For that, I remain grateful.

Despite the challenges, we loved Ealing and loved London. If the context is ever right again, who knows? We could absolutely see ourselves living there in the future.

We left London in early July 2017.

Entrepreneurship, English Clubs, and a New Chapter

After a months vacation in Turkey, the family arrived in Yekaterinburg in August 2017. I returned to Yekaterinburg with a new focus—building something of my own.

I began developing an e-commerce website, and after some trial and error, daxionmall.com was officially launched in September 2017. The first year was slow and, at times, disheartening—orders were sporadic, and progress was uncertain. Then, one day, a pin I posted on Pinterest gained unexpected traction. Traffic surged, reaching nearly 1,000,000 monthly views in the summer of 2018.

While DAXION mall™ has remained a small general store, it has continued to serve customers consistently for over eight years—a milestone I’m proud of.

In July 2018, I started the Yekaterinburg English Clubs—a series of informal English conversation groups open to the public. Sessions were held daily and promoted via YouTube and Instagram. Participants paid 500 rubles per session, and each meeting typically brought together 3 to 8 people at a local café or pub.

Our motto was simple: “Just Speak.”

At its peak, there were five to six sessions per week, scheduled across all seven days. The most popular slot, by far, was the Saturday morning club at 10 a.m., which it still is today.

In October 2019, I began exploring new professional opportunities—particularly in Moscow, where I relocated to be closer to potential employers and a larger market. Before departing, I handed over the operation of the Yekaterinburg English Clubs to one of my trusted facilitators—who continues to run them successfully to this day, seven years later.

However, by early December, it became clear that my Russian language skills were a significant barrier in pursuing roles outside of English-speaking environments. I made the decision to return to Stockholm and re-establish myself there professionally.

I left Russia in early December 2019.

When I arrived in Stockholm in early December 2019, I barely had time to catch my breath before things began to fall into place. At the airport, I met a friend—as agreed the day before. Over coffee, we caught up, and by the time we parted ways, I had both a place to stay and a job offer. A fantastic and unexpected start to my new chapter.

I worked with my friends for a short period before stepping into what would become a new experience, still ongoing: Chief Operating Officer at Qressida.

Qressida: A Journey of Growth and Purpose

When I joined Qressida Group AB in early 2020, I became its first employee. At the time, the company had a bold idea and a small portfolio—valued at just over 50 million SEK. What we didn’t have in resources, we made up for in vision.

Over the past five years, I’ve had the privilege to help shape Qressida into what it is becoming today. From the start, my role as Chief Operating Officer has been hands-on and wide-reaching. Among other things, I’ve contributed to:

- Defining the Qressida brand—not in visuals, but in behaviours, values, and ways of working

- Developing our strategic direction, guided by long-term thinking and purpose-driven growth

- Securing financing totalling nearly 800 million SEK, enabling us to fund housing projects and expand our property portfolio—now valued close to 1 billion SEK

While we’re still on the journey, we’ve come a long way.

Qressida is built on the belief that property development can do more than generate returns—it can serve people, shape communities, and drive meaningful progress. Our work is guided by principles of sustainability, inclusive design, financial responsibility, and a strong commitment to long-term value creation.

One of our more innovative concepts, Folkrätt™, reflects that ambition: a housing model that seeks to combine ownership, affordability, and community in a new kind of cooperative framework.

We are not yet where we aim to be—but we are moving in the right direction. Every project, every partnership, and every lesson along the way has brought us closer to realising that potential.

And for me personally, it’s been a deeply rewarding chapter—helping to build something that not only grows in numbers, but matters in people’s lives.

My Role as COO

As Chief Operating Officer, my work revolves around translating strategy into execution. I focus on driving operational efficiency while supporting growth, innovation, and long-term value creation. My background in risk management, staff planning, e-commerce, and process leadership has proven invaluable.

Every day, I work alongside a passionate and capable team. Together, we turn bold ideas into sustainable, livable realities. It’s a role that combines my love of systems and structure with a deeper sense of purpose—creating meaningful progress in real-world communities.

And that’s something I’m proud to be part of.

What the future holds, no one truly knows—and that’s exactly what makes it so incredibly inspiring to explore.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed shifts of historic proportions—transformations that arguably rival anything seen in previous generations. Three trends stand out to me more than others:

The speed of change is faster than ever before—and still accelerating. In areas like e-commerce, strategies that were cutting-edge just five years ago now feel outdated or irrelevant.

Today, the ability to learn, unlearn, and relearn is the new competitive edge. It’s not just about keeping up; it’s about adapting ahead of the curve, in a world where the curve keeps shifting.

Generation Z, and the even younger Generation Alpha, are emerging with completely new expectations—shaped by lifelong exposure to smartphones, social media, instant gratification, and digital convenience.

How they will choose to consume—why, where, and through which platforms—will redefine commerce and customer experience over the next decade. Their preferences will challenge existing business models and reward those who genuinely listen, adapt, and innovate.

The explosion of artificial intelligence has redefined what is possible—in business, education, design, decision-making, and beyond.

By 2025, AI has gone from being a buzzword to becoming an essential infrastructure layer of modern life. Whether it's personalised marketing, content creation, predictive logistics, or customer service automation—AI is reshaping the entire landscape.

The organisations that thrive will be those that understand how to leverage AI with purpose: not just to automate, but to enhance human creativity, decision-making, and agility.

We are now entering a time when creativity, adaptability, and ethical responsibility are more critical than ever.

It’s both humbling and exciting. And although none of us knows exactly what’s next, I believe the future belongs to the curious, the fast learners, and the courageous.

Let’s be among them.

AI Website Generator

FOLLOW ME!